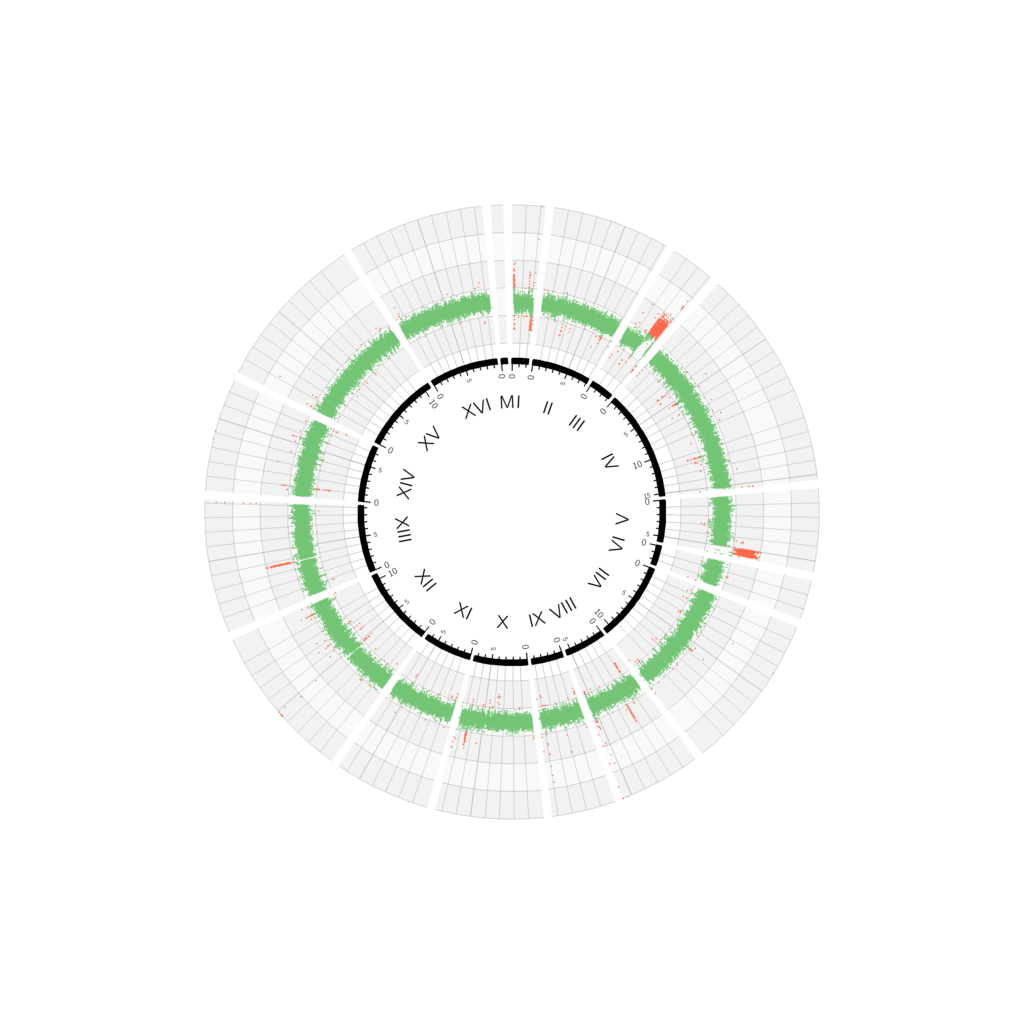

When sequencing whole genomes, the primary information obtained is the actual DNA sequence, but modern sequencing techniques carry embedded much more information. One of these is the relative abundance of sequencing reads that can be used to estimate the ploidy of each portion of the genome. In haploid yeast cells—the kind used in everyday experiments—each chromosome is present in one single copy. Yeast cells have 16 chromosomes, so the result would look more or less like the one on the left.

Relative sequencing coverage for a wild-type yeast genome

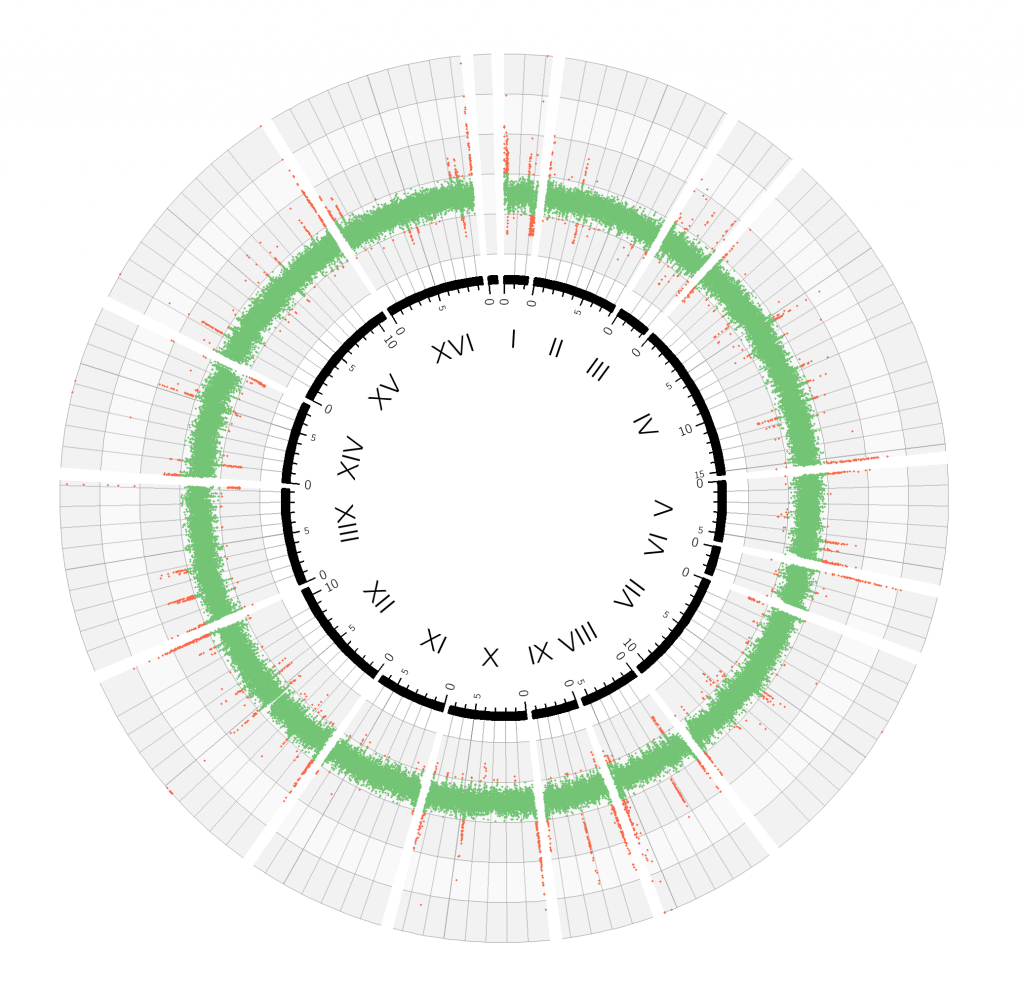

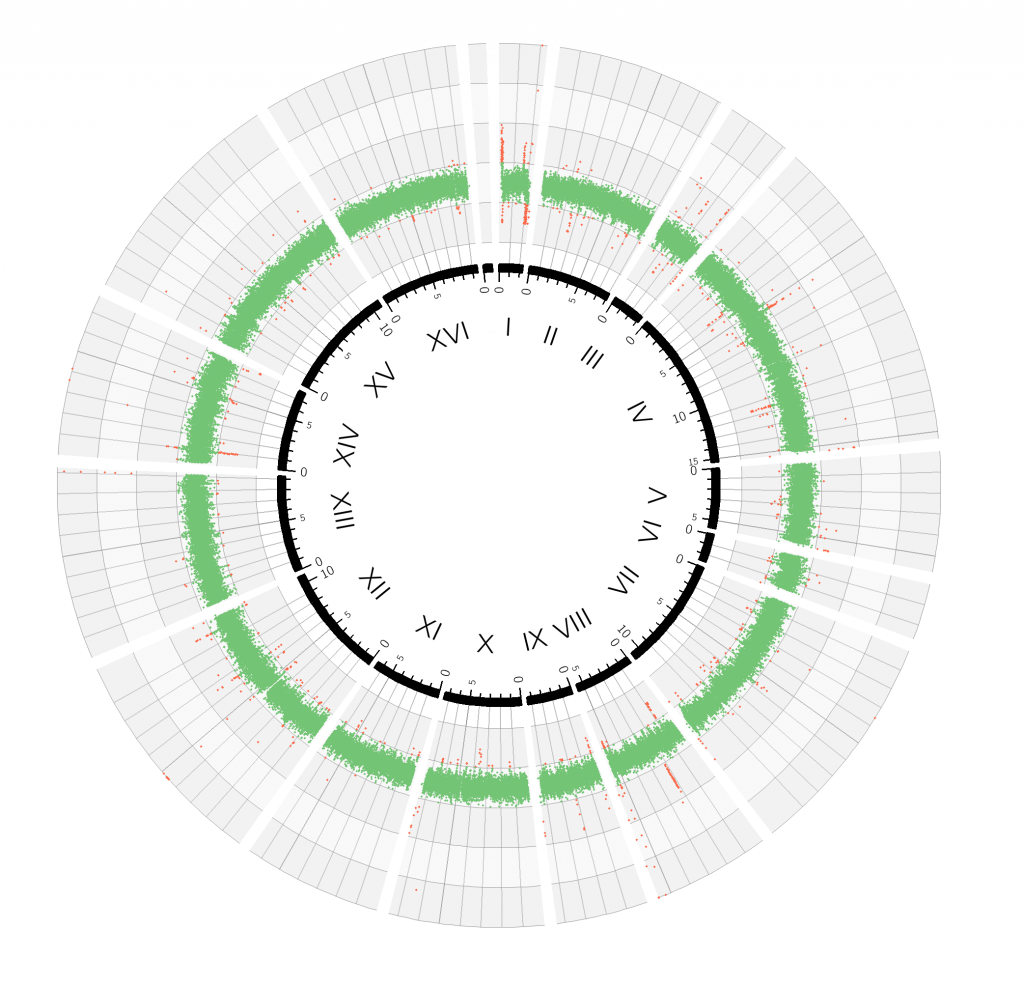

The same genome after filtering out telomeres, retrotransposons, and LTRs

The 16 chromosomes are arranged in a circle, from I to XVI, and the relative coverage, corresponding to the predicted ploidy for each 400-base-pair block, is plotted with increasing distance from the centre, and coloured in green if it falls in the interval 0.5–1.5. The green band shows that the majority of the genome is present in single copy. Red dots indicate that that particular 400-base-pair block was detected either more or less frequently than expected.

But why so many red dots? Genomes contain short DNA sequences repeated in tandem at telomeres (the ends of chromosomes) and indeed most red dots align at the beginning or end of chromosomes. Since only a few copies of these elements are present in the reference genome, these regions appear over-represented in the actual sequencing data. These artefacts—plus another category of artefacts generated by another group of interspersed repetitive regions (retrotransposons)—can be masked to produce a figure that is more representative of the sequenced genome.

In these conditions, it becomes much easier to spot when one fragment of a chromosome (or a whole chromosome) is duplicated. In this case twice the amount of reads for that particular region are produced by the sequencing process, doubling the sequencing depth for that particular region. In this strain, for example, the 3′ terminal part of chromosome III and V, and a narrow region in chromosome XIII have been duplicated.